The New Agenda for Peace: An Opportunity for Catalysing Member States’ Leadership in Conflict Prevention

This analysis aims to provide insights into the ongoing prevention debate at the global level. It further brings forward suggestions for Member States on how to move forward on the recommendations for prevention outlined in the New Agenda for Peace.

The commitment to advancing prevention in the multilateral system is not new. As far back as 2001, then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called for ‘NGOs with an interest in conflict prevention to organise an international conference on the role of civil society in conflict prevention’. This is how GPPAC was born to support the UN and its Member States in advancing prevention action globally. Later, the 2003 Report of the UN Secretary-General on Prevention inspired Member States to come together to adopt a General Assembly resolution on the prevention of armed conflict.

Today, the international community can advance conflict prevention strategies by learning from its history. But a united action by the UN Member States is required.

The time is now to reinvigorate a multilateral agreement on the need to invest politically and financially in prevention.

In 2021, the ‘Our Common Agenda’ Report by the UN Secretary-General gave hope for a renewed multilateral commitment to prevention because it emphasises conflict prevention as a central proposal. This prominence also resonates with Mr Guterres’ explicit commitment to conflict prevention since his appointment in 2016.

The expectation for many therefore was that the political agency of the UN could catalyse a conversation among Member States about reaffirming the multilateral commitment to prevention and strengthening inclusive national ownership in conflict prevention.

Now, the New Agenda for Peace (NA4P) – a key piece of the ‘Our Common Agenda’ puzzle for those dealing with peace and security matters – is out, certainly succeeding in generating a lot of conversations on what parts of this ambitious document will be taken forward, by whom and how.

Recommendations of the NA4P on prevention must be discussed by Member States to achieve a renewed multilateral agreement on prevention on terms agreeable by everyone.

Prevention continues to be under-prioritised by Member States.

While prevention has been an explicit commitment of the current and previous UN Secretary-Generals, Member States have been hesitant to step beyond a rhetorical commitment to prevention as it raises several sensitivities and questions about interventionism and the stigma of conflict.

Over time, the terminology of prevention in the global policy discourse got replaced by the language of sustaining peace. Sustaining peace is defined as ‘a goal and a process to build a common vision of a society, [...] which encompasses activities aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation, continuation and recurrence of conflict, addressing root causes, assisting parties to conflict to end hostilities, ensuring national reconciliation, and moving towards recovery, reconstruction and development’. This terminology, in a way, diluted the focus on prevention while keeping it within the definition.

In the dual General Assembly - Security Council resolutions on sustaining peace (S/RES/2282, S/RES/2558), Member States recognise ‘the responsibility for sustaining peace is broadly shared by the Government and all other national stakeholders’. However, the resolution does not come back to explain what this responsibility looks like in practice. It also does not use the language of the 2003 resolution, where the General Assembly extended an invitation to all Member States ‘to adopt national strategies, taking into account [...] multilateral and regional cooperation, mutual benefit, sovereign equality, transparency and confidence-building measures’. While it is generally clear what are the expectations from the UN system regarding sustaining peace, what implementing sustaining peace by Member States means remains unclear.

The NA4P recommends that Member States invest, politically and financially, in prevention.

The NA4P reiterates that Member States have the primary responsibility, as well as an ability unmatched by others, to prevent conflict and build peace in partnership with all of the society. What does this mean in practice?

Practically, the UN Secretary-General requested Member States to develop fully-funded national prevention strategies and strengthen national infrastructures for peace. This requires Member States to invest in developing prevention strategies in partnership with relevant stakeholders, including local peacebuilders who have championed prevention for decades. This request is not new. This is something Member States have already agreed to do in 2003, but not many took action.

Politically, the expected result of the conversations triggered by the NA4P is expected to send ‘a clear signal of a shift in focus to the national level’. As we see more nationally-driven designs of multilateral development, peacebuilding, and peacekeeping and the shift towards pluriversality, the ground may be favourable to use the Summit of the Future and its outcomes to formally recommit to prevention by all Member States rooted in inclusive national ownership.

Member States have opportunities to catalyse their leadership in conflict prevention.

First, lessons learned from other fields, such as the implementation of National Action Plans (NAPs) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) and National Development Plans (NDPs) aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer promising pathways to encourage multilateral agreement on prevention. Concretely, these plans demonstrate that unified global commitments do work to accelerate programmatic work at the country level, providing an opportunity for the whole of society to contribute to peace. Recently, the DFAT’s commitment to WPS translating into practical support for women-led prevention action led to the establishment of the Pacific Women Mediators Network.

Renewing a multilateral agreement on prevention in the Pact of the Future would send a strong signal to local peace actors and prevention experts to come together with their governments to design what prevention would look like in their contexts. It would open a possibility for all national stakeholders, including local peacebuilders, to work together with their governments to develop context-specific and comprehensive nationally-led prevention strategies that could unite many currently ad-hoc prevention projects.

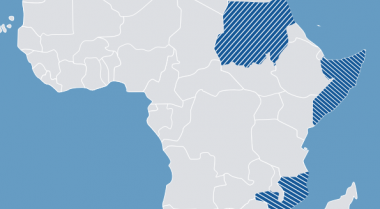

Second, even if a multilateral agreement on prevention looks unrealistic in the current political realm, other ways to maintain the conversation on prevention are possible. Practice reveals a number of lessons learned on advancing prevention at the national level that can provide learning for all Member States. GPPAC’s experiences with setting up early warning systems in the Southern African countries, supporting regional women mediators networks, including in the Pacific, and creating a civil society-led platform to address disputes and potential military aggression on the Korean Peninsula offer effective learning for Member States to consider adapting to their own context. NYU’s Center for International Cooperation (CIC) similarly highlights numerous examples of prevention efforts that work in Timor-Leste, Colombia, and the Gambia. Further, the recent initiative by Canada, Colombia, and Norway to bring to the Peacebuilding Commission their efforts to ensure reconciliation with and inclusion of the indigenous peoples is a clear signal that prevention is relevant for everyone, whether in the Global North or the Global South; it is not interventionist; and it requires action by all Member States.

In the lack of agreement on the policy language, at the very least, Member States, along with think tanks, civil society, and other partners, can come together to regularly exchange their prevention practices taking advantage of the convening function of the Peacebuilding Commission.

Third, strengthening the role of the General Assembly could also support addressing sensitivities around prevention. In the General Assembly, all Member States have a right to vote; therefore, they can jointly take the lead on what prevention action should look like in policy and practice. This requires listening to prevention experts and jointly reflecting on a set of guidelines for nationally-led prevention action, similar to the model adopted by ECOSOC in 2002. It will further take the prevention discussion away from the overwhelmed and currently divided Security Council and show the clear leadership of all Member States.

In the follow-up from the Pact of the Future, Member States should request the General Assembly to include in the provisional agenda of its eightieth session (in 2025) a specific item entitled ‘prevention of armed conflict’ or host a High-Level Meeting on nationally-led prevention efforts. In this format, Member States can consider a variety of ways to develop and implement long- and short-term measures and strategies aimed at preventing armed conflict and responsive to their own national contexts.

While the discussion on prevention remains one of the hardest topics in the international debate, the UN, its Member States, civil society, and other relevant actors generally agree that prevention is important to ‘save succeeding generations from the scourge of war’. The time is now for the UN Member States to move beyond rhetoric and take action toward a multilateral agreement and evolving dialogue on prevention!