Every voice matters for peace on the Korean Peninsula: Alison Lee on the importance of regional civil society coalition

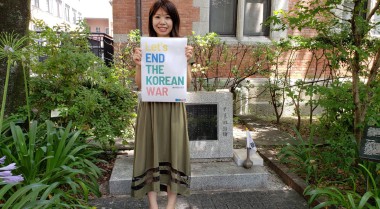

In this series, we highlight the diverse voices of people passionately building peace on the Korean Peninsula as part of the Ulaanbaatar Process (UBP). Named after the Mongolian capital in which it was officially launched in 2015, the Ulaanbaatar Process is a unique civil society dialogue for peace and stability in Northeast Asia (NEA). This interview features Alison Lee, originally from Hong Kong and currently based in Cambodia, where she works for the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS). As an expert in creating platforms for development of practical solutions for peace, she outlines how civil society can challenge political and militaristic rivalries in NEA.

Breaking the existing military narrative on the Korean Peninsula

Why is regional partnership so important for peacebuilding in Northeast Asia?

The governments, business sector and military have powerful cooperation and are the pillars of the system which creates instability and threats on the Korean Peninsula. Why then can’t we, people and organisations who want to prevent armed conflict, collaborate stronger and more powerful to build stability and peace?! It is now important to challenge the old narrative of the conflict on the Korean Peninsula, and create a crack in the official military narrative and offer something different, surely more peaceful.

The UBP provides such a platform for collaboration between those who want to prevent armed conflict. You have participated in the dialogue meetings in 2022 and 2023. What was your experience?

The deep dedication of all partners in the UBP to their work was very inspiring. Discussions and understanding of participants’ diverse perspectives were not always easy, because of their different political realities and sensitivities. Therefore, I was very impressed by the organiser's facilitation – it was great to see how constructive dialogue can successfully function in a diversity of backgrounds and perspectives.

How can the UBP contribute to decreasing current military tensions in NEA and open more channels for peacebuilding?

The most important is that the UBP remains a safe place for meetings and discussions in NEA, in the current tense situation in the region. We all have a great feeling of trust and safety in the UBP, which enables our open dialogue. Also, the UBP and GPPAC NEA are the avenues where representatives from both Koreas can meet and talk together. The representatives from the DPRK are marginalised in the international community, so when they have a safe platform to speak, they are very eager to connect with other people, and they want to be heard. I find it a very positive sign.

Civil society can't be silenced

How do you see the UBP could evolve in future and have a stronger influence on the peace process?

We need to build up an even broader coalition, which will include NGOs, activists, the business sector, educators and many more – we need to create a collective strong voice against war and militarisation. GPPAC NEA shows to the governments in the region and international institutions that civil society has a regional coalition in NEA, which can’t be ignored and can’t be silenced. We are here, we are relevant, and we want a more inclusive peace process.

Since you know the situation in Hong Kong and mainland China well, how do you think China, both its official and non-official side, could contribute more to the peace process on the Korean Peninsula?

If we want China to be a strong actor in the peace process in NEA, we need to acknowledge that the Chinese government aspires to have a leading role in maintaining regional stability. Global and regional stability is still the priority of the Chinese government, although it has its own way in dealing with regional problems. Unfortunately, the rivalry between China and the USA dominates the situation in NEA. Working together with civil society groups from China and its academia is important to understand Chinese society and to understand the current Chinese government.

This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the Korean War armistice agreement. Are you hopeful that the highly militarized situation on the Korean Peninsula can be changed and peace can finally come?

Actually, not so much. I have been learning in peacebuilding all these years that peace processes are hope-building processes. We need to find every glimpse of hope through all we do, wherever it is possible. The current situation in NEA is very challenging, but hope is practice, continuous practice. The more you practice, the more you see hope.

For more reflections on the prospects for peace on the Korean Peninsula, please read the publication issued in September 2022 as part of the Ulaanbaatar Process here: Peace and Security in Northeast Asia – The New Normal?