The Myth of Security: Why We Need to Place People Before Guns

After the Parklands school shooting in Florida, USA, President Trump, among others, suggested that armed teachers might prevent further tragedies. Some popular notions see this as common sense. The way to stop a gunman, they contend, is with more guns in the hands of ‘good guys'.

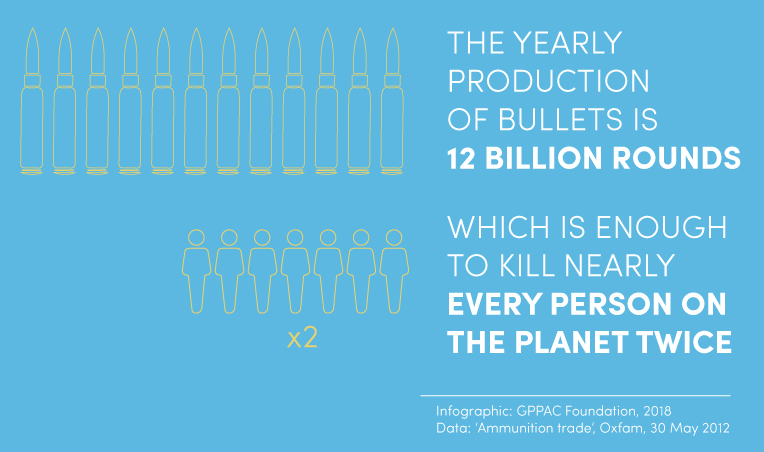

Wait, if more guns would solve our violence problem would it not have been solved decades ago since there are already more guns than people in the USA? With 12 billion rounds of small arms ammunition per year produced around the globe, enough to kill nearly every person on the planet twice, one would think we certainly would have enough arms and ammunition for peace.

Guns are currently the preferred currency of choice for ‘purchasing' national security. The global arms trade is $1.69 Trillion (US) per year. This arms approach to security is grossly mismatched with the security concerns of average citizens of any given country. Somehow the conversation on security must shift from the current "arms race-lite" to something that more accurately reflects a path to security that puts people first.

Overview of world military spending in 2016. Data and graphic: SIPRI

Human security gives that framework by developing inclusive processes that, from the very start of the security discussion, references the people most vulnerable to violence. Whereas national security is concerned with borders, territorial integrity and external threats, human security asks questions like: "what reduces our fears? Are people's needs met? And can we increase the dignity of all citizens?"

A few years ago, I did a project for Oxfam that aggregated data from a baseline survey in four provinces in Afghanistan. I was surprised that the security concerns that I expected to see as most pressing, were in fact, at the bottom of the list -if listed at all. I expected terrorism, local warlords and attacks from the Taliban or ISAF forces. Instead, what the residents in rural areas of the country were far more concerned with were minor conflicts with neighbors, family feuds and land disputes. This gap in what I, as an outsider, speculated and what local people actually experienced, could have increased insecurity if I had not taken the time to listen to their concerns.

Human security develops processes that listen to the voices impacted the greatest by violence trusting that these community members know best what their security needs are. In the case of Parklands, Florida, students and parents are very clear about what will make them more secure. How are lawmakers listening to the community and their desires? When powerful gun lobbies sway the minds of politicians, human security is minimized because the state is not accountable to the will of the people and this increases their sense of indignity.

Globally, security stakeholders, relying on hard power, need to develop coordinating bodies that value, respect and act on the concerns that the most vulnerable raise. How this is done will vary with each context. However, a few characteristics are common in the human security approach. The first is that people are at the core of the discussions, not tactics, political efficacy or resources. The second is that there are many approaches to security which must be coordinated. Thirdly these varied approaches to security must be appropriate for the context. And lastly, these approaches must be preventative oriented.

Costs of violence in 2016, in percentage of world GDP.

Data and graphic: Institute for Economics and Peace, Global Index 2017

Our collective insecurity is indeed overwhelming partly because violence is driving a $14.3 Trillion Dollar (US) a year hemorrhage in global resources according to the Institute of Economics for Peace. Imagine if even a percentage of what is spent on guns and responding to violence were used to enhance a people first approach to security.

By Jonathan Rudy -

Senior Advisor for Human Security at the Alliance for Peacebuilding, GPPAC Improving Practice Working Group Member and Peacemaker in Residence at the Center for Global Understanding and Peacemaking, Elizabethtown College