The 2020 Peacebuilding Architecture Review: How far are we from sustainable peace in communities?

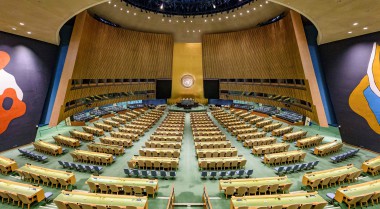

The 2020 UN Peacebuilding Architecture Review (PBAR) is the third comprehensive review of the Peacebuilding Architecture (PBA). The Review took stock of progress in the implementation of the resolutions on peacebuilding and sustaining peace, as opposed to re-envisioning existing concepts and frameworks.

The Review had a participatory character, inviting input from Member States, civil society and all parts of the UN system. And it had its impact. This approach was critical as it gathered the interest of many parts of the UN system to contribute to the process and think about how they could support peacebuilding work. The participatory approach has also helped the existing UN peacebuilding actors – the Peacebuilding Commission (PBC), the Peacebuilding Fund, and the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) – identify not only the areas of success but also areas where more action is needed.

However, one crucial question for us at GPPAC remains: What does the Review bring to local peacebuilders?

As the PBC Chair’s letter highlights, peacebuilding is only effective when impact is seen on the ground: this is exactly where local peacebuilders are located, where they work day in and day out.

Many local peacebuilders have not been engaged in the Review. A great number did not see the value of engagement in the consultations hosted by civil society and Member States. Others have engaged but continue to remain invisible on the global level and in the international policy space. This has been the case in the Americas, where local peacebuilders beyond those in Colombia and Venezuela struggle to access funding and engage in spaces where donors and policy-makers are both present. In the Middle East and North Africa, local on-the-ground peacebuilders are overshadowed by national civil society that has established relationships with the UN actors prior to the Review. At the same time, peacebuilding actors operating in frozen conflicts in the South Caucasus remain excluded from the peace dialogue.

Despite these challenges, there have also been success stories. The conversations in the Pacific led to civil society actors participating in the follow-up discussions both at the global level as well as at the regional level. This was the result of all partners’ commitment to multi-stakeholder engagement, as well as the understanding of every actors’ added value - as well as their limitations. Following up on this progress could eventually result in proper regional frameworks on peacebuilding, spaces for dialogue and innovative solutions.

The examples taken from the Americas, the Middle East, South Caucasus and the Pacific show how important it is to reflect on who was included in the discussions and who was excluded, as well as how meaningful the process was to all stakeholders involved.

Commitment to dialogue on all sides goes a long way. As we have seen from the Pacific, the commitment to understanding all partners’ capacity could lay the foundation for effective dialogue. Strengthening the UN capacity to develop and institutionalise this commitment is exactly the idea embedded in the UN System-Wide Community Engagement Guidelines on peacebuilding and sustaining peace. The Guidelines were published in the midst of the Review process and launched to support the UN actors in developing their engagement strategies.

The impact of peacebuilding work on the ground continues to be a mystery that only peacebuilders can solve.

Many questions emerged around the extent to which the UN peacebuilding infrastructure really produced an impact at the local level. It is known that the Peacebuilding Commission has played an active role in driving the peacebuilding action. It is also recognised that regional peacebuilding architecture is being operationalized to give more power to regional and national UN actors. We know that the 2018 recommendations of the Secretary-General are being implemented. The progress is tangible. As recognised by the Review, the critical obstacle for future progress is the lack of tangible progress in financing for peacebuilding.

However, do any of these findings reflect the experiences of local communities? Did the Review look into whether sustaining peace made a tangible impact on people in communities?

If we do not answer these questions, we risk having yet another Review in 2025 where all involved will praise their successes and point fingers to the next available donor.

The Review that local peacebuilders need focuses on their experiences in efforts to measure the effectiveness of peacebuilding work and responds to their experiences to bring peace closer to the local level.

From the 2020 Review, we can draw some key lessons that could inform the next “comprehensive” Review in 2025.

- PBAR processes and implementation efforts must not simply extract perspectives from local actors but listen and respond to their needs. The monitoring of peacebuilding needs to come from inclusive and diverse local peacebuilding networks. First, they can play an important role in connecting the human rights, development and peacebuilding sectors, using their collective networks and skills to address conflict at both the policy and implementation levels. Second, the steps needed to identify, in partnership with local communities, the kind of evidence useful to measure the impact of peacebuilding and sustaining peace. The partnerships, through the Community Engagement Guidelines, could be created to meaningfully engage with civil society to build informative and intentional partnerships.

- The outcomes of the Review must be more tangible. More could have been done by all actors involved in the Review to ensure local civil society inputs, where available, resulted in more tangible outcomes. Resolution 2558, or the Secretary-General’s Report on peacebuilding and sustaining peace, could have identified opportunities for follow-up actions with strategic timelines and specific requests. If the Secretary-General administers specific recommendations in the Women, Peace and Security Reports, the same standard should be upheld in the report on peacebuilding and sustaining peace.

- The Peacebuilding Commission could encourage the follow-up from the Review. Information received during the consultations remains meaningful and relevant. Efforts should be made to follow-up with consultation participants, to continue consultation processes where valuable, and provide more opportunities for those affected by conflict to contribute to policy processes and discussions.

Local peacebuilders are capable of identifying the impact at the local level: not only in capitals, but particularly on the most remote islands, in rural areas, and in contexts far off political radars. If the UN peacebuilding architecture is not working with these people and is unable to make sustainable changes for these local people on the ground why are we all even in this?